This article was originally published by SAM JACOBS on MAR 22, 2018 via businessinsider.com.au

- Research from ANZ suggests China’s residential property market is buffered from a material collapse.

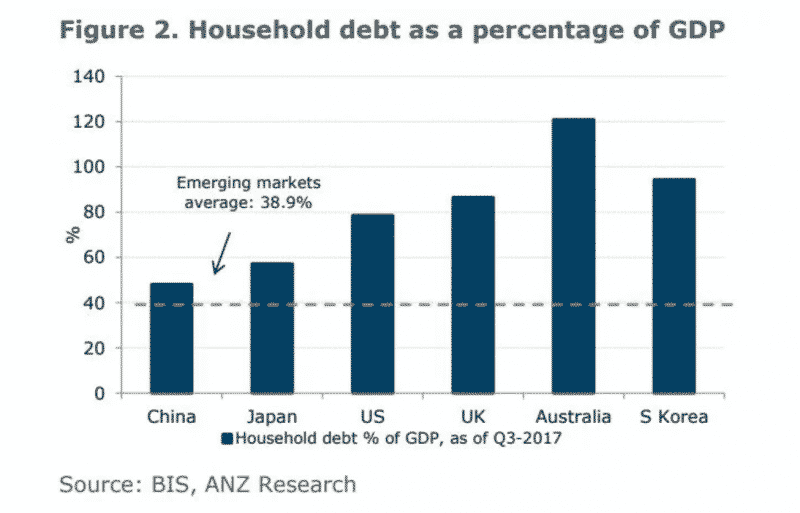

- Despite increased loan growth since 2015, China’s household debt-to-GDP ratio is still comparatively low.

- Analysis of loan-value-ratios suggests Chinese lenders can still absorb a significant house price correction.

Much has been written about the risks posed to China’s economy by the buildup of excessive leverage.

It’s an area the RBA raised concerns about in October last year, and Chinese authorities are continuing efforts to crack down on risky lending.

But analysis from ANZ suggests risks of a financial collapse are unlikely — at least when it comes to the residential property market.

ANZ senior China economist Betty Wang and colleague Kaushik Baidya based their thesis on two arguments:

- While mortgage growth has increased rapidly in the last three years, China’s debt-to-GDP ratio is still lower than many developed economies; and

- Based on China’s aggregate loan-to-value ratio, there’s room for a significant price correction before lenders come under material stress.

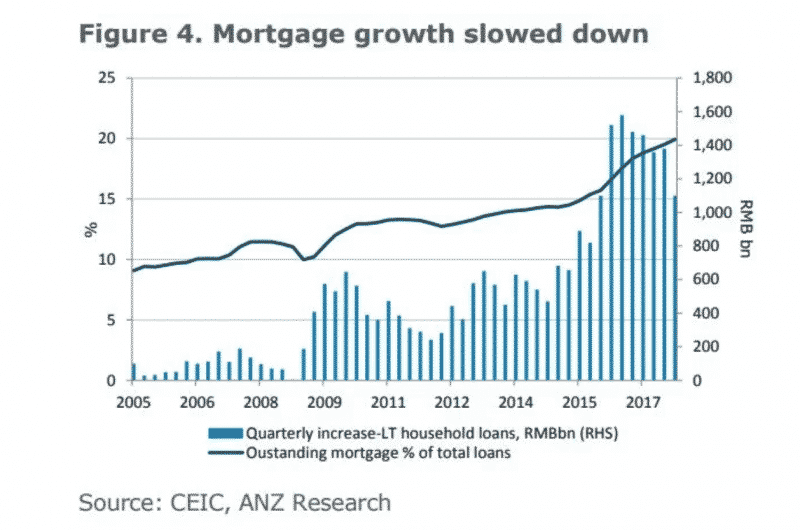

Residential housing mortgages in China amounted to 21.9 trillion yuan as at Q3 2017, representing an increase of about 27% a year since 2015.

And the rise in mortgage activity has seen total Chinese household debt rise to 48% of GDP as at Q3 2017 — up from 38.8% in 2015.

However, “while the rapid rise in household debt and mortgage has caught the attention of the Chinese government, we think concerns about property bubble have been over-stated”, said Wang and Baidya.

For one thing, China’s household debt-to-GDP ratio is still less than half that of Australia, which has a ratio of well over 100%:

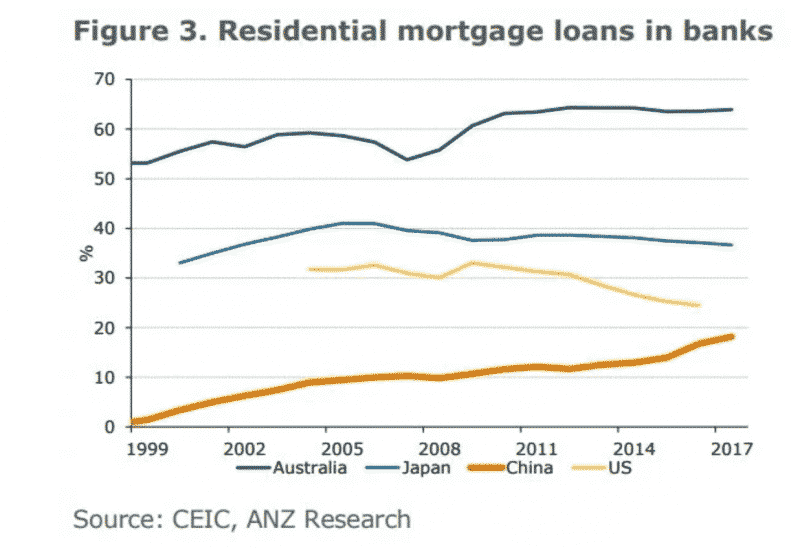

In addition, the analysts said China’s banking sector has a broader loan portfolio, and is thus less exposed to residential mortgages.

“For the banking sector, the share of home mortgages stood at 18% of total loans in 2017, one third of that in Australia and 70% of that in the US,” the analysts said.

Wang and Baidya added that an assessment of loan-to-value (LTV) ratios on issued mortgages is a more effective stress-test than debt-to-GDP. A higher LTV means more money is required from the borrower up front.

Mortgage data in China is hard to come by so the analysts constructed an indicative model based on available information.

The pair used new building sales as a proxy for estimating mortgage issuance, and applied a model based on one-year lending rates for data before 2009 (when mortgage rates data wasn’t released).

They also estimated mortgage length and rebuilt the National Bureau of Statistics’ property price index back to 2004 to get a more accurate picture of collateral household wealth.

“The weighted average LTV ratio was 33.8% as of 2017, according to our calculations. It means that the market value of collaterals (i.e. underlying properties) is almost two times the outstanding loans,” the analysts said.

“We find that all cohorts can bear a substantial 50% decline in property prices (if not bigger) without running into negative equity.”

“We expect that many mortgages drawn in early years have been paid up by now. At the same time, prices of the underlying properties doubled from early 2000s, substantially boosting the market value of the collateral.”

They said the rapid rise in mortgage growth over the last three years adds an increased level of risk to the market.

However, the LTV ratio of more recent loans is a stringent 40% — much higher than the 20% requirement for loans issued before that.

Furthermore, in line with the recent crackdown on excessive leverage by Chinese authorities, annual mortgage growth has slowed to 22%, down from 36% in 2016.

“As long as the collateral value of these parts of mortgage is not falling significantly, the government’s cooling measures since 2016 will prevent the risk from further escalation,” the analysts said.